The Loewe Foundation Craft Prize, founded in 2016, is already a venerable institution. Established by Loewe creative director Jonathan Anderson, it highlights just how far craft has come – not only in technique but in reputation. If ceramics, tapestry or glass are increasingly regarded as “art”, it is in part due to prizes like this. When it launched, “there was no prize globally for craft, ultimately”, says Anderson, whose own obsession began when he was 21, with a salad bowl by Lucie Rie. It was hard to get people to apply at first, he says, but this year they received 3,900 submissions. “It has become an award that has changed people’s careers,” says Anderson. Adds jury member Deyan Sudjic, director emeritus of the Design Museum: “The lines between design, art and craft are eroding.”

The 2024 finalists © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

This year’s Prize featured 30 finalists from 16 countries and regions. The winner, Mexico’s Andrés Anza, was announced yesterday evening for I only know what I have seen, a glowing, looming ceramic piece that could be a cactus or a sea creature from the deep; he was chosen by a jury including Anderson, Loewe Foundation president Celia Loewe, Sudjic, ceramicist Magdalene Odundo and last year’s winner, Eriko Inazaki. “It was a very intense deliberation,” says Anderson, but the decision was unanimous. (The actor Aubrey Plaza presented Anza with his prize.)

I only know what I have seen, by Andrés Anza © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

From left: Jonathan Anderson, 2024 winner Andrés Anza and actor Aubrey Plaza, who presented the award © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

Here are some takeaways from this year’s edition.

Those cow’s intestines look good on you

The Prize always has a good line in surprising materials. This year, we have both rubber tyres and sea shells, but the pièce de resistance is Wings of the Blue Bird by Eunmi Chun – an elegant oversized turquoise necklace whose “feathers” are, in fact, made of cow’s small intestine.

Wings of the Blue Bird, by Eunmi Chun © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

Chun, who is from the Republic of Korea, had been looking for a new, sustainable material to work with; something she could take “from the earth”, and return to it. A cow’s small intestine is 18 metres long, but she still needed several to make her “wings”, constructed once the intestines had been dried and dyed, then sewn together. And yes, you can wear it.

You can touch! (Maybe)

Craft is defined by the materials used, but it’s a fine line as to whether it can be tactile. Japan’s Ikuya Sagara positively encourages you to touch Reminiscent Wind, an elegant slab of rice straw and Japanese grass that has been thatched onto a wooden board. Brushing it with your fingers is like touching particularly high-end toast.

Reminiscent Wind, by Ikuya Sagara © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

Other makers wince if you get too near. Emmanuel Boos has received a worthy mention for Comme un lego, a narrow coffee table in porcelain, tenmoku black and wood, which can be assembled and reassembled thanks to its 98 loose, hollow bricks.

(In foreground) Comme un lego, by Emmanuel Boos © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

Harmony of Grigris, by Ange Dakouo © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

But it’s not something you should play with – the black glaze is incredibly hard to achieve on porcelain, and can easily be scratched by clumsy fingers. Then there’s Ange Dakouo’s Harmony of Grigris, a lace work that has protective qualities, according to the Malian artist; a “grigris”. Considering its venerable quality, stroking its tassels is best avoided.

Always come back to nature

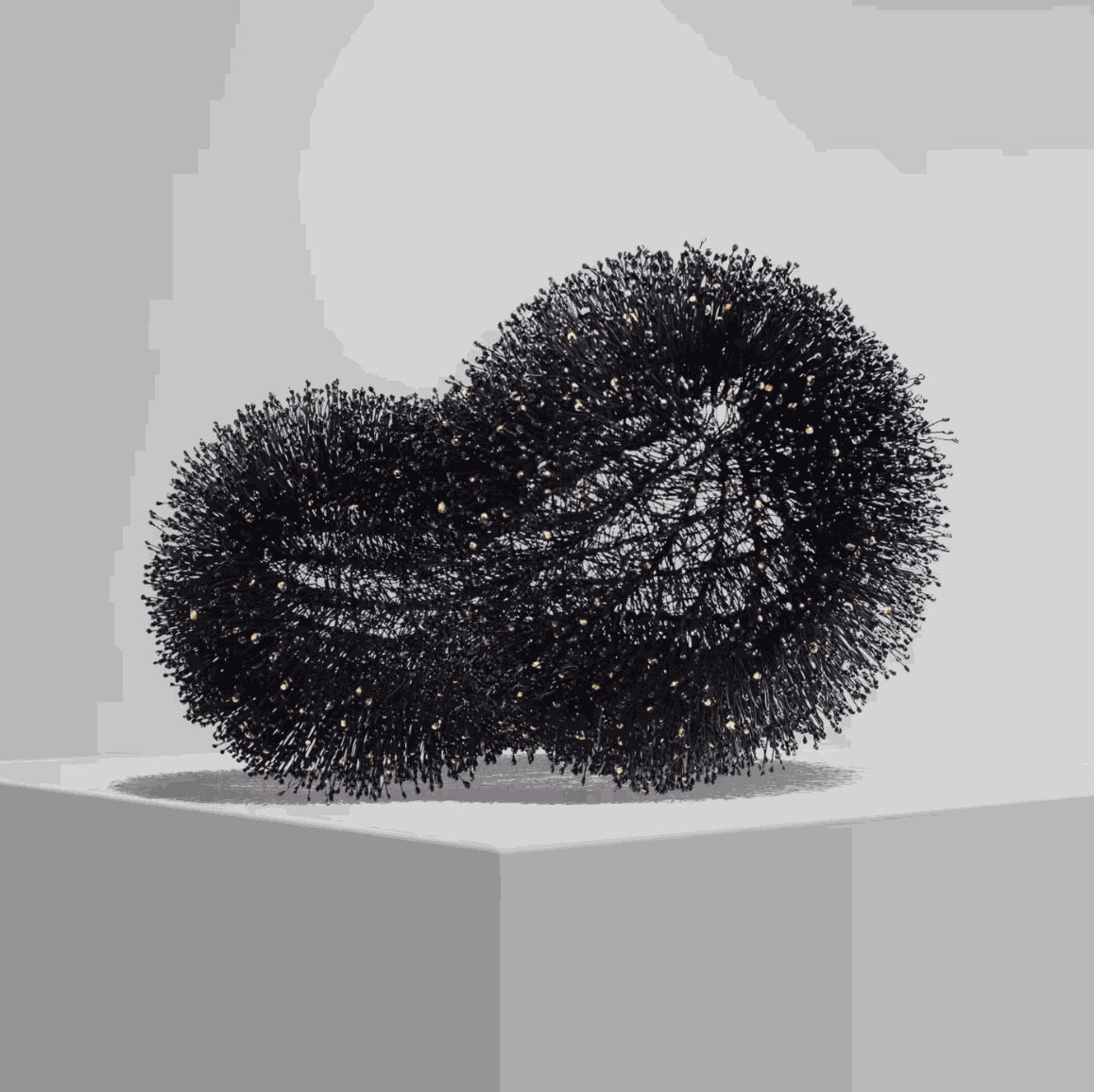

A profusion of shapes this year call to mind the natural world: Racso Jugarap’s Echinoid, a spiky concoction of galvanised iron, gold leaf and resin resembles a disco sea-urchin; Holly Shell, by Alison Croney Moses, made from curved holly wood, evokes a seashell; Weon Rhee’s Primitive Structures (Botanical) is a small coffee table that looks like two mushrooms; while the winner, Andrés Anza, has produced a totemic, prickly piece that could be either plant or beast.

Echinoid, by Racso Jugarap © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

Holly Shell, by Alison Croney Moses © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

The observation that the surface evokes an oversized lychee doesn’t shock Anza: “I get that a lot,” he sighs.

A message matters

Craft isn’t immune to politics. Raven Halfmoon’s monumental piece Weeping Willow Women, made from ceramic glaze, is daubed in a bloody red – a reference to the murder of Indigenous women in the US (Halfmoon has Caddo Nation ancestors, and uses Caddo ceramic traditions here).

From left: Primitive Structures (Botanical), by Weon Rhee. Weeping Willow Women, by Raven Halfmoon © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

Kazuhiro Toyama’s large bowl is made from cracked copper, speaking to “social and environmental collapse”.

A cracked copper bowl by Kazuhiro Toyama © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

Displaced, by Kevin Grey © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

And Kevin Grey’s Displaced was inspired by the Birmingham resident hearing how many people were displaced around the world. The circularity of the piece, almost a hollowed-out bowl, references these peoples’ unending journey; its hard, jagged edges, made in bronze, nod to the toughness of the conditions.

Super-size jewellery, please

Norman Weber’s 3D-printed plastic and acrylic brooches © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

In a series of vitrines, the three “jeweller” finalists go under the spotlight, and the items are defiantly oddball. Each has fun playing with size and colour. Norman Weber uses 3D-printed plastic and acrylic to produce exuberant, pop-coloured brooches; Karl Fritsch’s Pukana is a suite of five rings where synthetic gemstones protrude almost haphazardly from the bands.

Pukana, by Karl Fritsch © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

Still Life, by Miki Asai © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

One of the special mentions, Japan’s Miki Asai, has produced work that at first seems minute – tiny evocations of vases and pots. It’s called Still Life. The work has been painstaking, the artist pulling seashells apart, then applying them onto the surface with tweezers. When you realise that these are rings you can wear on one finger or even two, it turns out they are, in fact, rather large.

Totems are in...

The totem is back in fashion; here, both the winner and Saar Scheerlings’ Talisman Sculpture: The Column evoke its classic structure. Yet neither lays claim to any great spiritual practice.

Talisman Sculpture: The Column, by Saar Scheerlings © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

In the case of Scheerlings, the real story is in the fabric used – her “totem” is assembled from dozens of cut-up pieces of old mattresses, which she has covered in sleeves made from old French linen and bound together with string. She bought 30 mattresses from a man who had bought them from old hotels, thinking he could resell them – “but nobody wants old mattresses”, she says.

…as are African threads

A whole generation of artists, often from the African diaspora, are weaving threads into their work, evoking their culture and heritage. The Prize’s finalists included three artists who have produced very different types of wall hanging.

Ozioma Onuzulike’s “ceramic tapestry” © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

CY15, by Patrick Bongoy © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

Nigeria’s Ozioma Onuzulike has created a large “ceramic tapestry” made from handcrafted clay palm-kernel shells woven together with copper wire, nodding to prestigious African textiles like aso-oke. Patrick Bongoy’s CY15 weaves together something very different: recycled rubber from old car tyres, old metal valves and wire. And Dakouo’s Harmony of Grigris is based on a grid of briquettes covered with newspaper, then overlaid with cotton thread and cowrie shells. He hopes it protects his fellow Malians in a country torn apart by Jihadism. As for the newspaper itself, it’s a nod to his father, who was a printer – so when you glimpse the words “Julie Burchill” amongst the threads, there is apparently no deeper meaning.

Japan and Korea continue to raise the bar

Japan and Korea (along with the US) had the most finalists this year, with five each. These are countries where craft is established and respected – almost every day, says Eriko Inazaki, the Japanese winner of last year’s edition. “Craft is perceived in a very different way there,” says Anderson. “It’s more protected.” Why do the Japanese do well? “The will – the determination!” says Inazaki. The Japanese, she says, “have a will to see things through”.

The jury for the 2024 prize © Courtesy Loewe Foundation

Sheila Loewe – from the fifth generation of the Loewe family that founded the brand in Madrid in 1846 – says it was particularly good to see Anza win this year, as it has been harder to find entrants from Latin America or India. “A winner from Mexico will give the world a very, very strong message,” says Loewe, “that the world is big – it’s not always the same places having the most beautiful pieces.”