The Craft Prize That Became a Runaway HitCourtesy of Loewe

The Craft Prize That Became a Runaway HitCourtesy of LoeweOn Tuesday night in Paris, inside the expansive Palais de Tokyo, a warm and enthusiastic group of artists, editors, designers, and curators—Pharrell and Rick Owens among them—gathered to celebrate the handmade. The event was The Loewe Foundation Craft Prize, an annual competition and exhibition featuring independent makers from around the world who are chosen for their unique skills in media ranging from woodworking, basket weaving, and ceramics to textile art and jewelry design. This year is focused on works that speak to organic and biomorphic forms, as well as works that incorporate recycled materials.

A grant prize of €50,000 is awarded to the winner and this is the 7th year since the Craft Prize was founded by Jonathan Anderson and the Loewe Foundation’s president, Sheila Loewe. When it began, craftmakers were hesitant to be part of the competition; this year, 3,900 makers applied. “To think that we have some 3,000 applications every year now is insane,” Anderson said in a press junket on Tuesday, shortly before the winner was announced. “What I find really fascinating is the number of people globally working within the craft field.” Loewe echoed the excitement around how much of an impact the Prize and the foundation are making: “To think about the Craft Prize becoming a long-lasting, authentic project is a happy, beautiful dream.”

Patrick Bongoy, Democratic Republic of the Congo‘CY15’, recycled rubber, inner tubes, silicone, metal valves and wire, 1800 x 1750 x 100 mm. 2023Courtesy of Loewe

Patrick Bongoy, Democratic Republic of the Congo‘CY15’, recycled rubber, inner tubes, silicone, metal valves and wire, 1800 x 1750 x 100 mm. 2023Courtesy of LoeweAfter guests made their way through the serene, silver tile-detailed exhibition space to view the work of the 30 finalists, everyone gathered to hear the panel of 12 jury members, which included Anderson, Loewe, architect Patricia Urquiola, The Met Museum’s Curator of Modern Architecture, Design and Decorative Arts Abraham Thomas, and last year’s Craft Prize winner Eriko Inazaki announce the winner and honorable mentions. They were sculpture artist and jewelry designer Miki Asai from Japan, designer Emmanuel Boos from France, and sculpture artist Heechan Kim from Korea. This was the first year there were three instead of one or two, as Anderson noted earlier that day, because the judges' debate was “heated,” and the choice was almost too difficult to make.

Alison Croney Moses, United States

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Holly Shell’, holly wood veneer and glue, 770 x 300 x 370 mm.

2023

Andrés Anza, Mexico

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘I only know what I have seen’, ceramics, 450 x 400 x 1500 mm.

2023

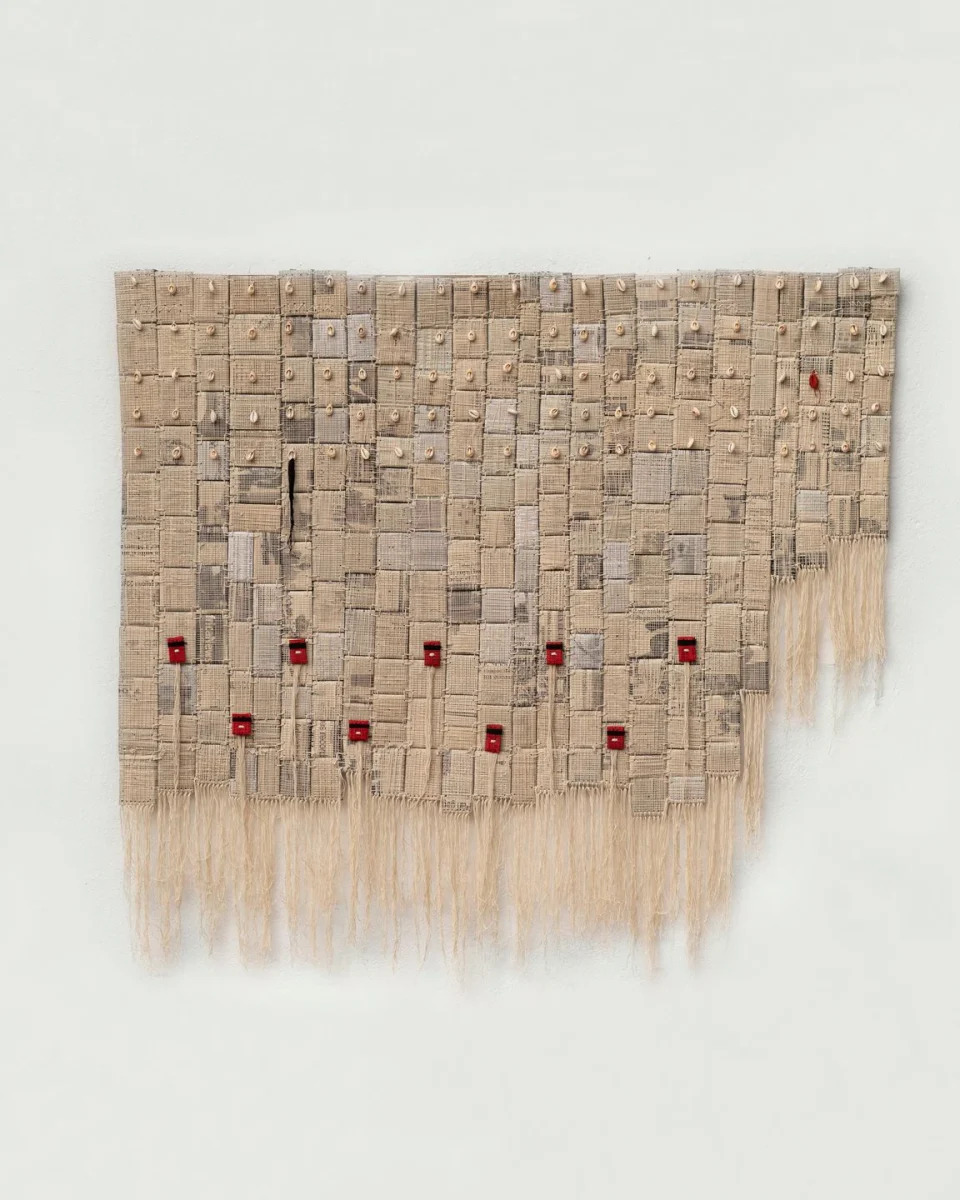

Ange Dakouo, Mali

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Harmony of Grigris’, cardboard, newspaper, cotton thread, acrylic and cowrie shell, 1630 x

1530 x 10 mm.

2023

Aya Oki, United States

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Bloom IX’, glass, 380 x 350 x 380 mm.

2023

Chun Tai Chen, Taiwan Region

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘In Simplicty’, paper, dye, glue, aluminium, stainless steel and brass, various dimensions.

2023

Debaroun (Dahyeon Yoo), Republic of Korea

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Harmony’, vegetable tanned leather, 250 x 130 x 130 mm.

2023

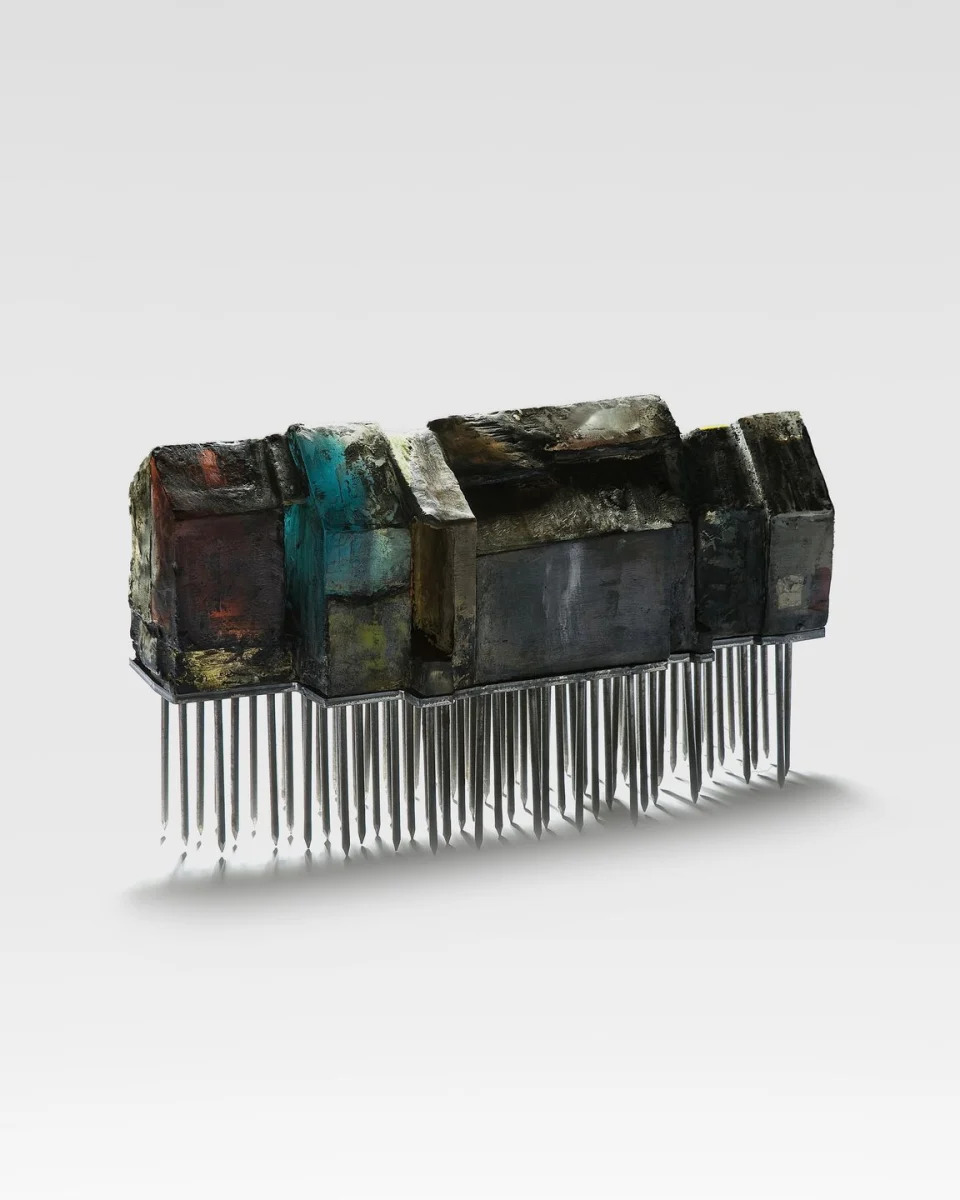

emmanuel boos, France

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Coffee table ‘Comme un lego’’, porcelain, tenmoku black and wood, 670 x 1760 x 380 mm.

2023

Eunmi Chun, Republic of Korea

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Wings of the Blue Bird’, cow’s small intestine, thread and ink, 320 x 610 x 35 mm.

2019

Ferne Jacobs, United States

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Origins’, coiled and twined waxed linen thread, 445 x 1295 x 100 mm.

2018

Gaku Nakane, Japan

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Seed’, clay, 620 x 610 x 495 mm.

2023

Heechan Kim, Republic of Korea

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘#16’, ash wood and copper wire, 1067 x 813 x 813 mm.

2023

Hiroshi Kaneyasu, Japan

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Unformed Outline’, urushi lacquer, plaster and hemp, 1020 x 970 x 80 mm.

2021

Ikuya Sagara, Japan

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Reminiscent Wind’, rice straw, Japanese pampas grass and wood, 855 x 450 x 60 mm.

2023

Jeremy Frey, United States

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Symphony in Ash’, black ash, sweet grass and synthetic dye, 305 x 305 x 560 mm.

2022

Karl Fritsch, New Zealand

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Pukana’, silver, gold and synthetic gemstones, various dimensions.

2020

Kazuhiro Toyama, Japan

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Biophilia: Celestial Shaped Vessel’, copper, 700 x 700 x 210 mm.

2023

Ken Eastman, United Kingdom

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Don’t get around much anymore’, stoneware clay, slips and oxides, 340 x 360 x 650 mm.

2023

Kevin Grey, United Kingdom

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Displaced’, 1.2 mm bronze Sheet, 520 x 520 x 170 mm.

2022

Kira Kim, Republic of Korea

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Standing House’, glass and steel, 387 x 140 x 240 mm.

2023

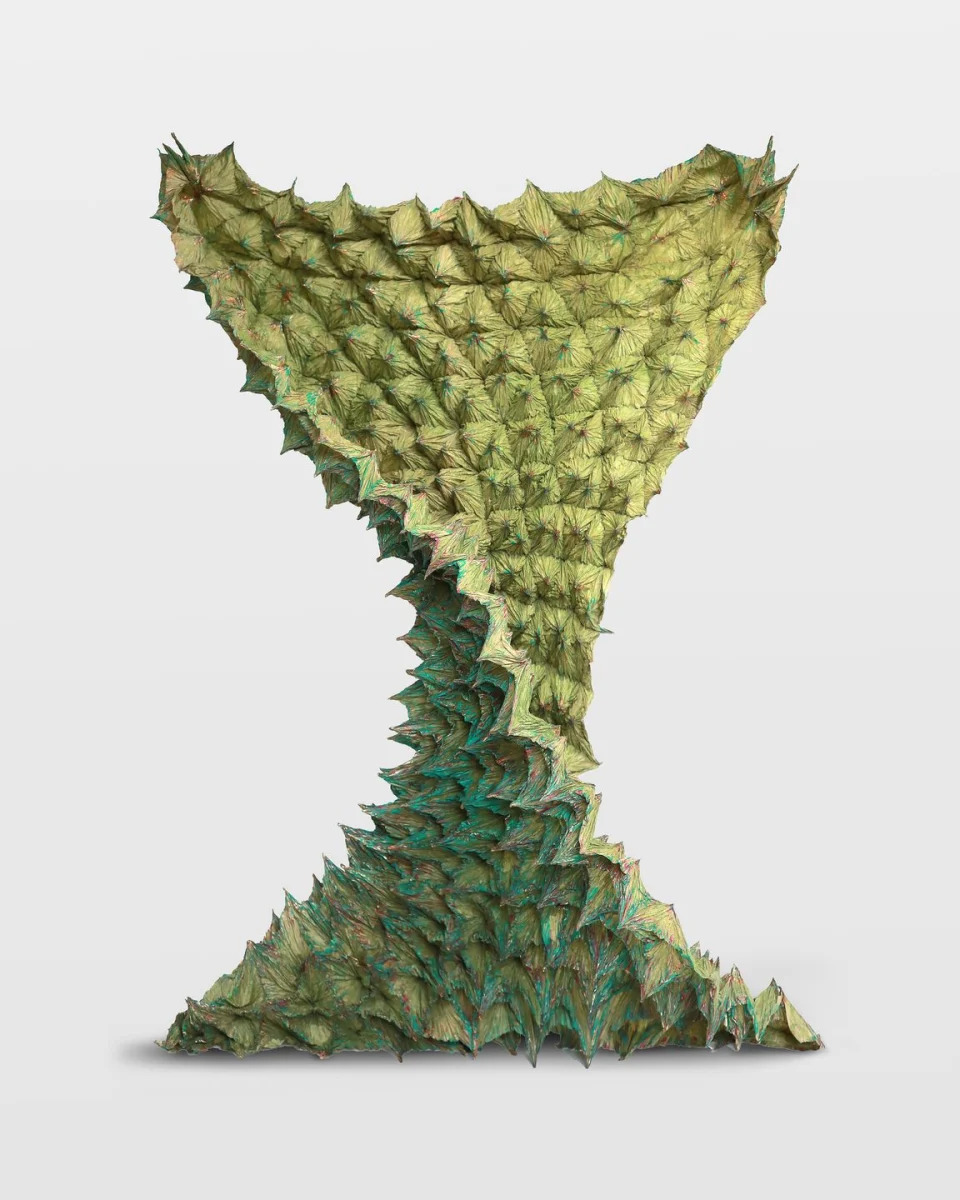

Luis Santos Montes, Spain

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Cristalización Orgánica Esmeralda’, paper, MTC and inks, variable dimensions.

2023

Miki Asai, Japan

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Still Life’, wood, paper, kashu, eggshell, seashell and mineral pigment, various dimensions.

2023

Norman Weber, Germany

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Juwel’, plastic and acrylic paint, various dimensions.

2021-2022

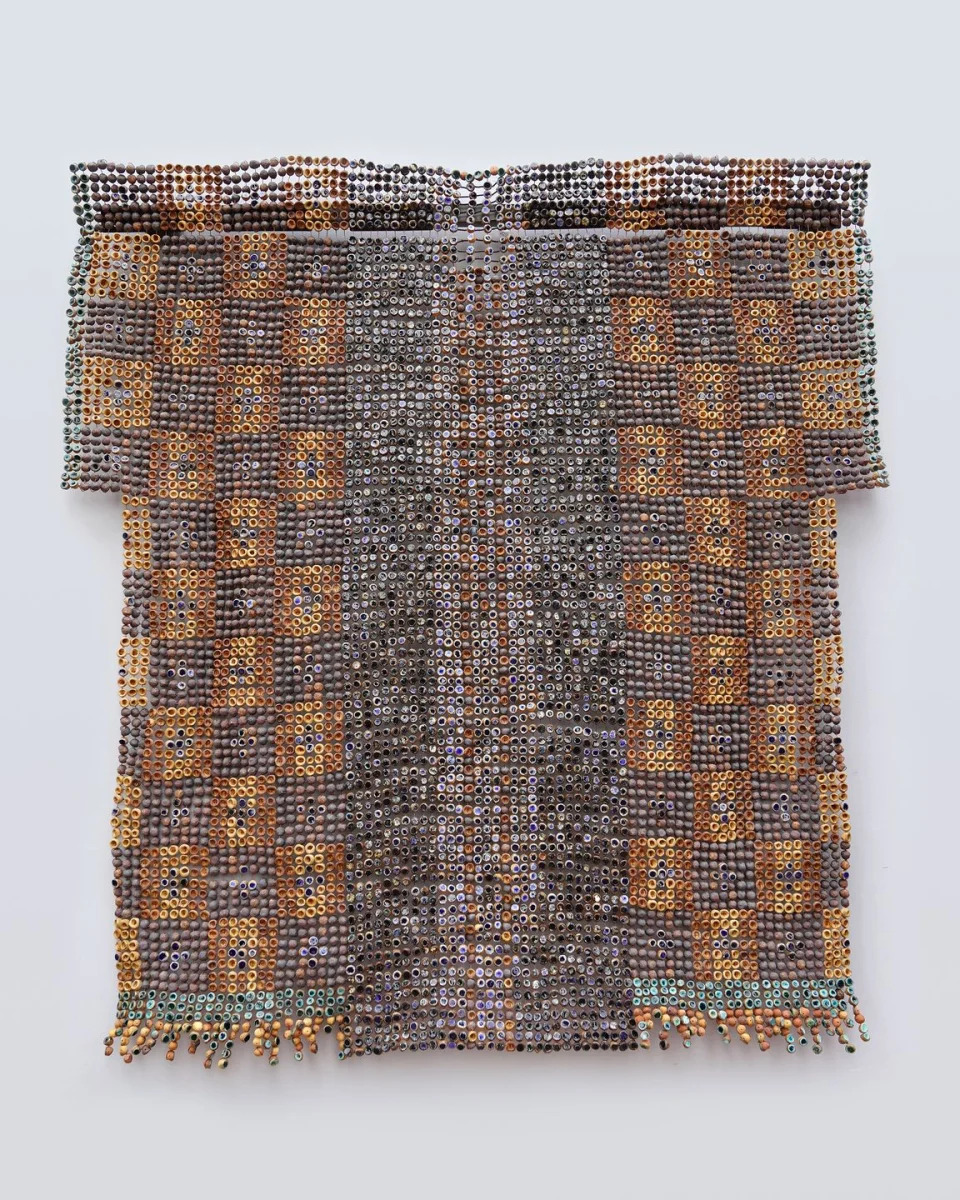

Ozioma Onuzulike, Nigeria

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Embroidered Royal Jumper for Peter Obi’, clay, ash glaze, recycled glass, engobe and copper wire, 2240 x 2300 x 120 mm.

2023

Patrick Bongoy, Democratic Republic of the Congo

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘CY15’, recycled rubber, inner tubes, silicone, metal valves and wire, 1800 x 1750 x 100 mm.

2023

Polly Adams Sutton, United States

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Ebb Tide’, cedar bark, binder cane and magnet wire, 355 x 310 x 430 mm.

2023

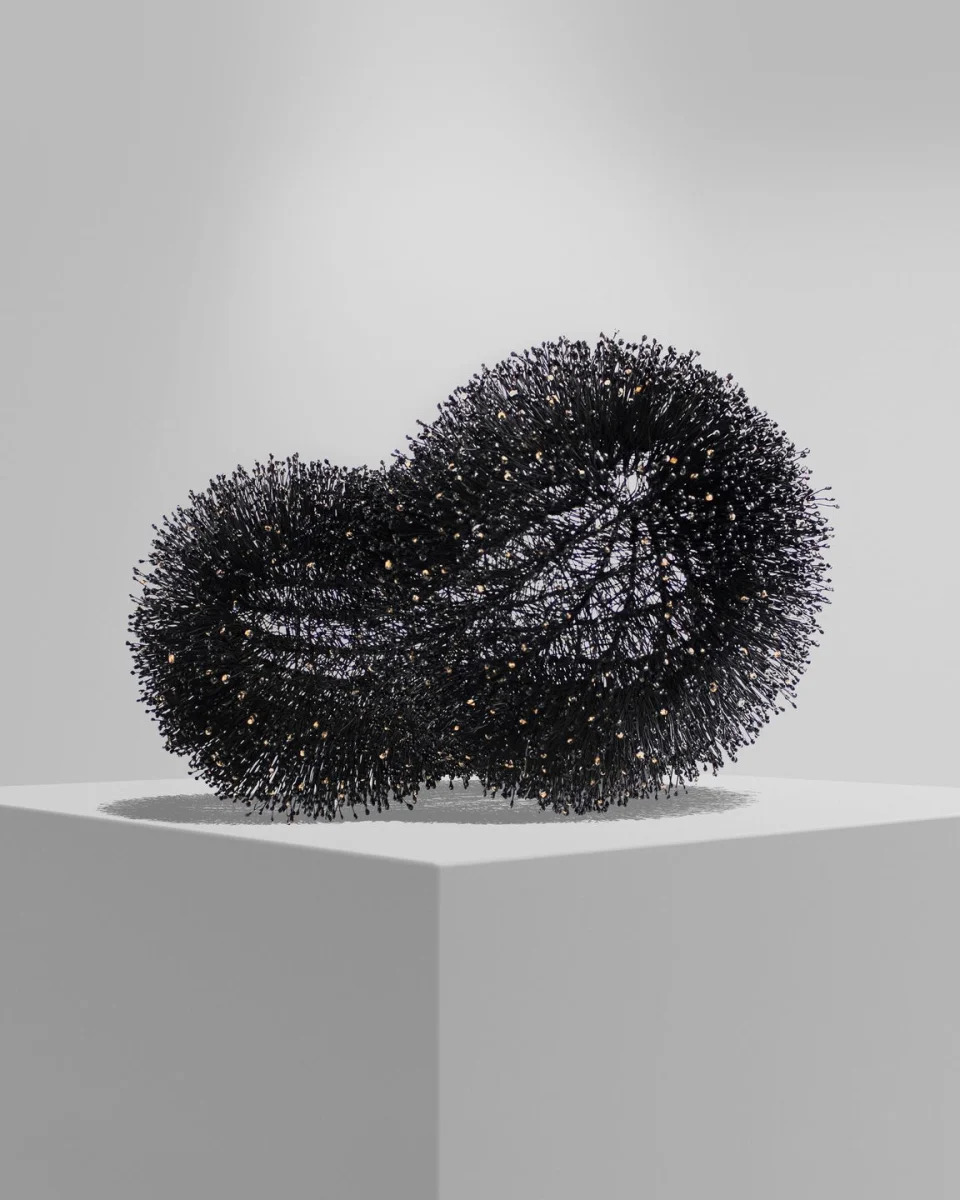

Racso Jugarap, Philippines

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Echinoid’, galvanised iron, gold leaf and resin, 420 x 270 x 250 mm.

2023

Raven Halfmoon, United States

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Weeping Willow Women’, ceramic and glaze, 1830 x 1170 x 1830 mm.

2022

Saar Scheerlings, Netherlands

Photo credit: Courtesy of Loewe

Photo credit: Courtesy of Loewe‘Talisman Sculpture: The Column’, foam, old French linen, various yarns, oakwood and metal, 480 x 240 x 2450 mm.

2023

Weon Rhee (Jongwon Lee), Republic of Korea

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE‘Primitive Structures (Botanical)’, PSL Beam (recycled wood), pearl coloured pigment and green pigment, 1370 x 790 x 440 mm.

2023

Yuefeng He, Mainland China

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE

Photo credit: COURTESY OF LOEWE2020

After brief speeches from Loewe and Anderson, actress Aubrey Plaza came to the stage to award the prize to the winner: Andrés Anza, a young artist who hails from Mexico and won for his globular, otherworldly ceramic sculpture titled ‘I only know what I have seen.’

Anderson is passionate about empowering makers in various corners of the globe, not only by providing financial support through grants but also by giving them a visible space to express and promote their talents and handwork. “For me, it’s about putting them forward so that the brand doesn’t have to speak. It’s about using the facilities that we have to allow them to explore and experiment, and it also really helps when they’re given another avenue to sell their work.”

Anderson is adamant about making sure that the Craft Prize and the collaborative projects that it yields feel purposeful and woven naturally into the foundation of the brand. “If you don’t embed yourself into it, then it is just a transparent marketing tool, whereas this is something which is going through the entire company.”

Aya Oki, United States ‘Bloom IX’, glass, 380 x 350 x 380 mm. 2023Courtesy of Loewe

Aya Oki, United States ‘Bloom IX’, glass, 380 x 350 x 380 mm. 2023Courtesy of LoeweHis own long love affair with craft started with a salad bowl by the British ceramicist Lucy Rie that he saw at an auction many years ago. “I became completely obsessed,” he said. “Still to this day, I still collect her work.”

It’s all very personal to him, as evidenced by his playful, artful work for Loewe.. He has a deep desire to create a narrative around craft that “flattens hierarchies,” elevating the medium to the same playing field as fine art or architecture.

And while so much of craftwork is about tradition, Anderson is looking ahead, anticipating what the future of artisanship may look like and how he and Loewe can help preserve and grow it. Surprisingly, he believes that the future of craft is anchored in new technologies. Anderson noted that “when you look at TikTok or Instagram, people are fascinated by the idea of makers.” He added, “I think people find it therapeutic to watch people make things. Some of our highest-performing videos [at Loewe] are to do with people making something. And I think there is an innate curiosity within society at the moment to reconnect to the making process and for us to understand why we perceive artistic value in something.” Engaging with this curiosity and feeding it is exactly what Anderson intends with the Craft Prize, and with the brand overall. As he noted, “It’s a good way for Loewe to be quite grounded as a brand.”

Yuefeng He, Mainland China ‘Bamboo Rock’, bamboo, lacquer, tile ash and linen, 1400 x 800 x 600 mm. 2020Courtesy of Loewe

Yuefeng He, Mainland China ‘Bamboo Rock’, bamboo, lacquer, tile ash and linen, 1400 x 800 x 600 mm. 2020Courtesy of LoeweThroughout the day of the event, the vibe in the Palais de Tokyo was a sweet one. The artists mingled with one another and connected through their rarified work. Alison Croney Moses, who is based in Boston and brought her 5-year-old daughter with her to Paris, remarked, “I found my people here, people who understand the intersection of art and craft. We make these things because we want to make them. It doesn’t need to have traditional functionality or form.” Her daughter wore a bright pink frilly tutu dress and sat against the wall just next to Moses’s mesmerizing, spiraling wood veneer sculpture titled “Holy Shell,” which hung from the ceiling. She was using colorful clay to build her own tiny totem, a baby-sized sculpture that sort of resembled something by Ugo Rondinone. It was one of many tender moments at the Loewe Craft Prize, maybe not so visible to everyone there but important nonetheless. As Moses spoke about her work, her wide-eyed daughter stomped over to her and proudly showed her what she’d crafted in the corner of the room. “She really loves to make things,” said her mom with a smile.