The Boston Public Art Triennial will display dozens of pieces downtown and in neighborhoods across the city, reflecting much-changed appetites for public art

For decades – even a century or more – public art in Boston has been easy to

define: By material (granite, marble, bronze), by format (human figures, usually

on horseback, usually male) and by theme (historic, historic, and historic; the

older the better).

But in recent years — slowly, sometimes painfully — a new vision of Boston has begun to

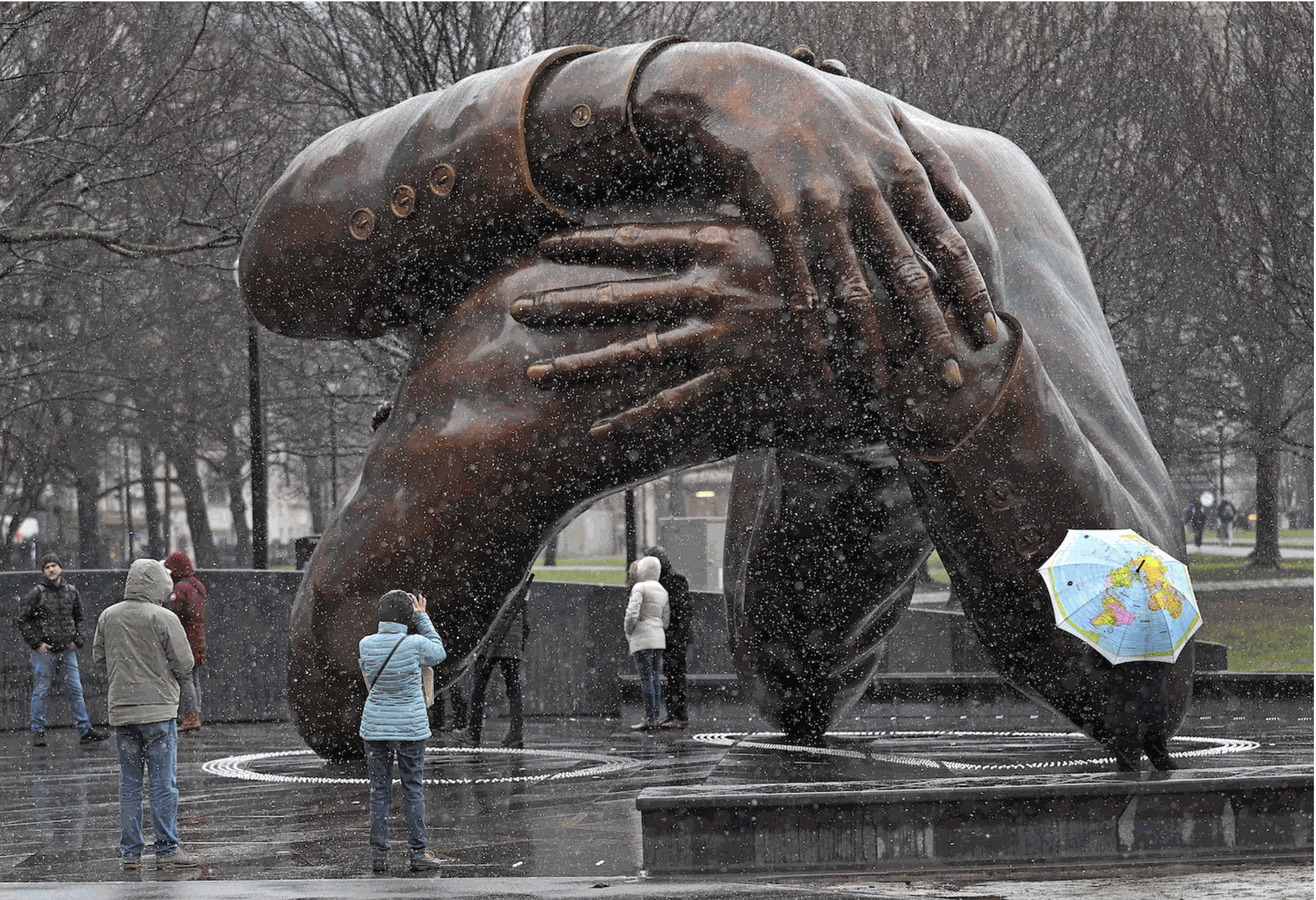

emerge. That was never more clear than in late 2022, when “The Embrace,

” Hank Willis Thomas’s confounding, colossal tangle of hands and arms arrived on Boston

Common. A memorial to Martin Luther Jr.and Coretta Scott King, it loudly proclaimed a

shift that had labored to express itself in whispers.

While Boston has surely lagged its urban peers asit stood pat on an old vision of itself,

it’s about to make up for lost time: Next month, the Boston Public Art Triennialwill

arrive with two dozennew works displayed downtown and across the city, in

neighborhoods from Charlestown to Mattapan. Partnered with the city’s venerable art

museums as well as the city itself, the Triennial’s ambitions fit with a city refashioning a

new sense of self.

“It really does feel like a completely different city than 10 years ago, ” said Kate Gilbert,

the Triennial’s executive director. “There’s just a greater aptitude for experimentation

We’re over our fear of the ephemeral — of a lot of those old fears, I think.”

Specifics will be made public next month, but installations will run a gamut of form and

idea, from large-scale sculptureto videoto performances, by artists both local and far-

flung: Boston’s Alison Croney Mosesand Stephen Hamilton, Nicolas Galanin, a widely

celebrated Indigenous artist from Alaska.

For Hamilton, whose project will be installed in Roxbury, the Triennial “is not something

I could have imagined when I graduated (from MassArt) in 2009,” he said. “But I’m also

looking to the future. How can an event like this help us grow?”

Kate Gilbert, executive director of the Boston Public Art Triennial, in the lobby of the Boston Public Library where one of many public artworks will be installed next month. JOHN TLUMACKI/GLOBE STAFF

He might look to the rare feat of cooperation the Triennial has achieved: The Museum of

Fine Arts, the Institute of Contemporary Art, andthe Isabella Stewart Gardner

Museum are all taking part and the City of Boston will contribute its own slate of

projects, too.

Artist Stephen Hamilton in his Allston studio as he prepares for the Boston Triennial. LANE TURNER/GLOBE STAFF

“The idea, really, is to have an experiment happening out in public,” said Karin

Goodfellow, the city’s Director of Transformative Art and Monuments. “We’re testing

civic space in different ways, and trying to find different pathways to release some

assumptions and find ways to approach what we do that feels authentic and organic to

the city’s cultures.”

Boston’s reputation as an international cultural center is rooted in its past, and its public

art landscape reflects that: George Washington on horseback in the Public Garden;

Paul Revereat the North End Church.Making inroads to set-in-stone narratives isn’t

easy, but Gilbert knows the terrain. In 2015, she founded the Triennial’s precursor, Now

+ There, a non-profit with a mission of promoting contemporary public art.

Now + There’s projects were everything Boston’s public realm was not: Ephemeral.

Contemporary. Oblique. Diverse. Some works were predicated on play; others, live

flower gardens. Projects were often made for neighborhoods the city’s gilded cultural

reputation rarely touched: Roxbury, Chinatown, Dorchester, Grove Hall -- a priority to

which the Triennial has remained faithful.

The Triennial will re-up its citywide program every three years, and its aim is not modest:

To be a permanent emblem of a new Boston that’s waited so long for its time to come.

Partnerships are key to that vision. At the Museum of Fine Arts,the museum’s

contribution to the Triennial effort flanks its grand entrance: A pair of shimmering

chromium sculptures by the Mohawk artist Alan Michelsoncalled “The Knowledge

Keepers.” They depict Julia Marden and Andre StrongBearHeart Gaines Jr., living

Indigenous people with expertise in their cultures’ history.

A view of "The Knowledge Keepers" looking out from the Museum of Fine Arts. Left: "Andre," by Alan Michelson, 2024. Right, "Appeal to the Great Spirit, " Cyrus E. Dallin, 1909. MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON

The museum’s contribution to a new way of seeing an old city, “The Knowledge Keepers”

is heavy with symbolism of a city in the throes of change. A tacit response to “Appeal to

the Great Spirit,

” Cyrus Dallin’s 1909 bronze sculpture of an Indigenous man on

horseback, arms spread wide. The contrast is not subtle: Dallin’s piece, a forlorn Native

American nowoften seen as a cliched pastiche, has sat on the front lawn of the

museum since 1912; it’s a bleak relic next to Michelson’s vibrant representation of

contemporary people, living their lives in the now.

Meeting with Triennial staff over time, “it’s been clear to me that they were always

approaching us with this idea that (the Triennial) could be a real change agent in the way

in which Bostonians think about the art that’s around them in the city,” said Ian Alteveer,

chair of the MFA’s Contemporary Art Department, who commissioned the work. “I’m

thrilled, and I’m also learning from this process myself.”

At the City of Boston, Goodfellow is stewarding the city’s own attempt at ephemeral,

experimental public culture as part of the Monuments Project, funded with a $3 million

grant from the Mellon Foundation.

"The Embrace," by Hank Willis Thomas, on a snowy day in 2023 shortly after it was installed on Boston Common. The artwork commemorates Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King, and depicts four intertwined arms, representing the hug they shared after he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. DAVID L. RYAN/GLOBE STAFF

The programdistributed $1 millionof that grant among fivelocal curatorial partners,

the Triennial included. The city also has a roster of its own projects, to be announced

later this month. Called “Un-monument,” its aim is to counterweigh Boston’s

traditional civic narrative with projects that elevate long-overlooked episodes and people.

Though it may feel sudden, new ways of thinking about public space – who it’s for, what

it can say, what it can do – are the product of a long, slow evolution. Unease around

monuments in particular as simplistic emblems of complex histories had been simmering

for years when, in 2020, the murder of George Floyd brought sudden, urgent action.

The statue of Robert E. Lee, altered by artists and protesters, at Lee Circle in Richmond, Va., June 20, 2020, before it was taken down. The monument became a rallying point for a national takedown movement after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. CARLOS BERNATE/NYT

In Richmond, Virginia, a bronze statue of Robert E. Lee astride a horse became the hub

of a nationwide takedown movement. Installed in 1890 to give symbolic form to the

racist policies of the Jim Crow South, the Lee statue was removed in 2021.

Boston’s history is less fractious than the segregated South; but the urgency of the

moment brought its painful racial divides to the surface. Its clearest manifestation was

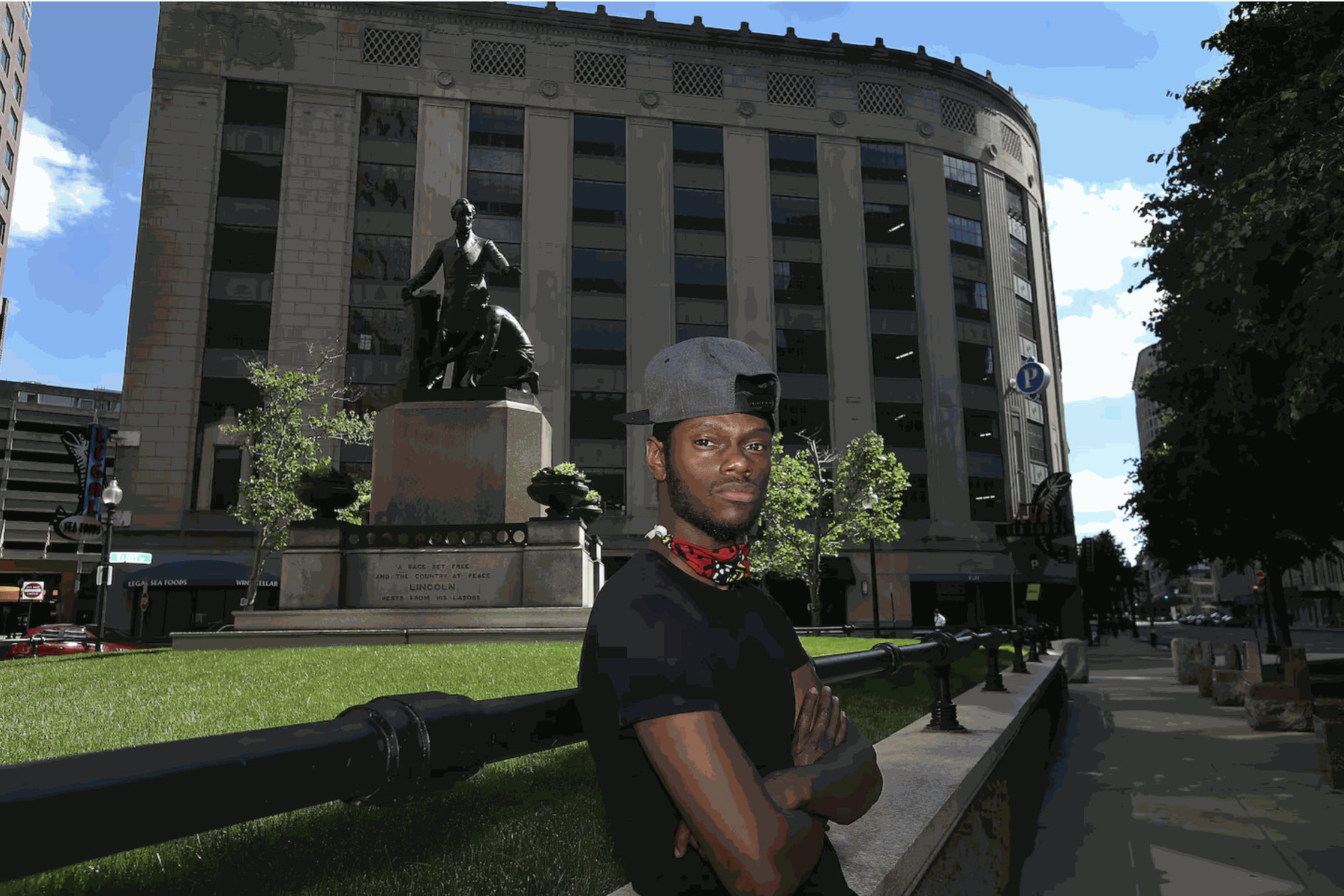

an effort to remove Thomas Ball’s “The Emancipation Group,” a 19th century bronze

in Park Square of Abraham Lincoln annointing freedom upon the enslaved Black man

crouched before him. A thousands-strong petition led by artist Tory Bullock prompted

the city’s Boston Art Commission to vote unanimously to remove it in June 2020.

Tory Bullock, who started a movement to remove "The Emancipation Group" monument of Lincoln towering over an enslaved person in 2020. BARRY CHIN/GLOBE STAFF

That same month in the North End, vandals beheaded a marble statute of Christopher

Columbus, beloved in the Italian community but reviled by many as a symbol of

European colonization. The statue was removed a few days later. Months later, on

Indigenous People’s Day (the former Columbus Day), a blank, human-shaped figure

took its placeon the empty stone plinth. Installed by Boston artist Cedric Douglas, he

projected the images of an array of local icons as apublic honor: Elma Lewis, the iconic

Roxbury arts educator; Mel King, the long-time Civil Rights activist; Jessie “Little Doe”

Baird, a Native American linguist who helped preserve and revive the Wampanoag

language.

He called it “The People’s Memorial Project,

” and Goodfellowcould see its potential. As

part of the city’s Unmonument efforts this summer, Douglas will extend the project he

began in 2020; he’ll be out in public asking Bostonians what should occupy the empty

plinth where “The Emancipation Project” stood. “These are the kinds of projects that we

mean to inform us going forward,” Goodfellow said.

The installation occupied the former site of the Christopher Columbus statue, which was beheaded in June. @ARAMPHOTO